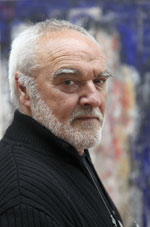

VALENTIN OMAN

Aktuell

Vita

Arbeiten auf Leinwand

Arbeiten auf Papier

Öffentlicher Raum

Texte zu Oman

Filme zu Oman

Kontakt

ecce oman

Andrea Zsutty

The first meeting with Valentin Oman seemed like a theater production. Clothed in a white kaftan he appeared in the studio door – very few people could seem more exotic or more strange in the middle of a Carinthian country village with its memorial to the fallen soldiers of World War I, with its guest house “Kirchenwirt” and the appendant church. It quickly becomes clear that a different spiritual wind wafts here. The first impression reveals that the artist, his private living space and his work create a unity. A few days later, in his Vienna studio, this impression is confirmed in a long conversation that is the basis for this contribution to the catalogue, and broadens the view towards Oman’s cosmos.

Mr. Oman, in what context are your works created? Are there certain situations, times or moods that you need for working?

Earlier in my life I used to wait to be „kissed by my muse“, to become inspired, but for many years now I go to the studio early and basically work all day. My stimulation is classical music.

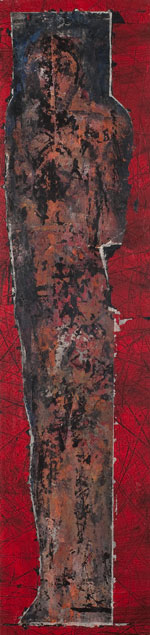

The largest part of your work concerns people. Many figures develop from the prints of earlier murals. Would you kindly explain this form of working?

I actually began with this technique when designing the church in Tanzenberg, where I worked for a year on the walls of the presbytery with the theme “Requiem for Homo Sapiens”. Using a continual repetition of the painting process on the wall and following up with a de-collage, I attempted to show the multiplicity of the figures. And then by detaching the layers of colors, my panels developed, my so-called “veronica of mankind”.

How does the combination of spontaneity and control play out in your work process?

Chance plays a big role in removing the material from the wall. The more layers on the background, the richer the result. I exert control by the exact cutting and then making a collage of the parts.

Many figures are fragments put together that were painted on plastic wrap

How did you come to this technique?

I had an experience in Paris that led me to experiment with plastic wrap. Scratches on a window painted white in a shop that was being renovated – I was fascinated by what appeared from the outside to be a large-surface abstract black/white graphic. After experimenting for a long time with various materials, I finally got the result I wanted on the plastic wrap.

From the beginning of your artistic carrier you have been interested above all in graphics. You call yourself more of a graphic artist than a painter. Why?

In the beginning I was preoccupied with print graphics and black-white techniques. This interest has remained with me, as I can express myself best in black-white. There are cycles that stay in black-white for a long time, until the hunger for colors reappears.

Whether in sacred or profane themes, the issues you confront are always existence and transcience, memory and forgetting. Everything goes around the themes of death, religion, temporality. Where does love play a role?

In the cycles „Man and Woman“ or „Traces of the Heart“, the theme of love comes through. I use titles as suggestions, deciphering the pictures I leave to the observers. Love and religiosity are for me such private themes that no clearer statements will come from me.

You like to experiment a lot in your choice of techniques. Is it sensual joy or the uncertainty of the result of each experiment that drives your creativity?

For me, the panel pictures aren’t “dead” for a long time, because one can always experiment with new materials. So for me the delight in the work is there till the very end.

How do you feel about the concept „all-rounder“ that Peter Baum coined for you and your work?

I don’t have a probem with it, but I do with the name „Master of Sacral Art“, as was printed in a newspaper recently. I do not want to differentiate between the sacred and the profane in my work.

Many of your works are covered with lettering. Are you interested in the interplay of structuring and over-explaining?

Yes, that’s exactly it. And there’s something else as well. If one of my figures becomes too clear, then it will be structured again with the lettering. It becomes partially covered and more secretive.

What intrinsic value does the text have for you regarding the picture. It is message, stylistics or a purely aesthetic decision?

The lettering is not a decorative element for me. These are texts that interest me and that I want to archive for myself. These can be very different texts. Newspaper articles as well as, for example, the preface by Mario Simmel to the Wehrmacht Exhibition in Vienna, or texts from the Bible. Of course, the texts are used to make innuendos about one’s own position.

You travel a lot, above all in the Mid-Eastern countries and cultures, to Morocco, Oman, Yemen, etc. You make sketch pages, remarkable because of the luminous choice of colors. What fascination do these foreign cultures produce in you?

Here I can position myself in the form of an illustrator of the “old school”. These illustrated trips and their results are very important for me because they cannot be repeated in the studio and they help me to overcome the occasional austerity of my figures. They remain, however, illustrations of my travels in a closed section.

You also document your impressions while traveling by photographing. Interesting double exposures resulted out of this. How did you come to photography and what possibilities for expression do you find there that painting and graphics don’t provide for you?

There are motifs that I couldn’t implement in the form I want in my painting. I try to create a multi-layering with double-exposure that is similar to my panel pictures. The content is not visible at first glance, but rather has to be deciphered by the observer.

Would you call yourself a political artist?

I would say yes. I’m always concerned with political developments. Titles like “Croatia I” and “Piraner Way of the Cross” in which I concern myself with the war in ex-Yugoslavia document this. Another example is “My lai” (Vietnam war) or somewhat more current, the work “Twin Towers”.

Your resistance to the politics of a certain Carinthian governor was expressed in a 13-year refusal to exhibit in Carinthia, was not loud but rather very quiet and very personal. How do you relate to the current political situation of Austria?

Regarding the discussion about putting up bilingual Carinthian place names – which, by the way, is a matter for the Austrian federal government that has defaulted on implementing article 7 of the Austrian State Treaty for decades –

I’m concerned about the preservation of Slovene cultural values. My contribution to the preservation of this culture are two works at the University of Klagenfurt: a stela or pillar cast in iron with bilingual place names, and the artistic design of the translators’ booth using bilingual place names.

Your exhibition has the Slovene title Nazej, which translated means something like “return” “come back”. What does it mean to you to show your work in Carinthia again?

It is wonderful that this is possible in Villach/Beljak, which should be self-evident in all of Carinthia. When I was awarded the Culture Prize of the City of Villach/Beljak, I promised Mayor Helmut Mazenreiter that I would have my first single exhibition after my politically motivated absence here. I know of course that the political spirit in Carinthia has not changed, but nevertheless I’m happy about my „nazej“ in Villach /Beljak.